I have a new paper out in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers with Andrea Ballatore and Shilad Sen. In it, we ask (and empirically answer) questions about the the local-ness versus foreign-ness of content that Google serves up to people around the world. You can access the full paper below.

Ballatore, A., Graham, M., and Sen, S. 2017. Digital Hegemonies: The Localness of Search Engine Results. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. DOI:10.1080/24694452.2017.1308240.

Please also note that I’m currently hiring a Researcher in Digital Geography if you’d like to work with me on similar topics!

Summary (taken from the paper’s conclusions):

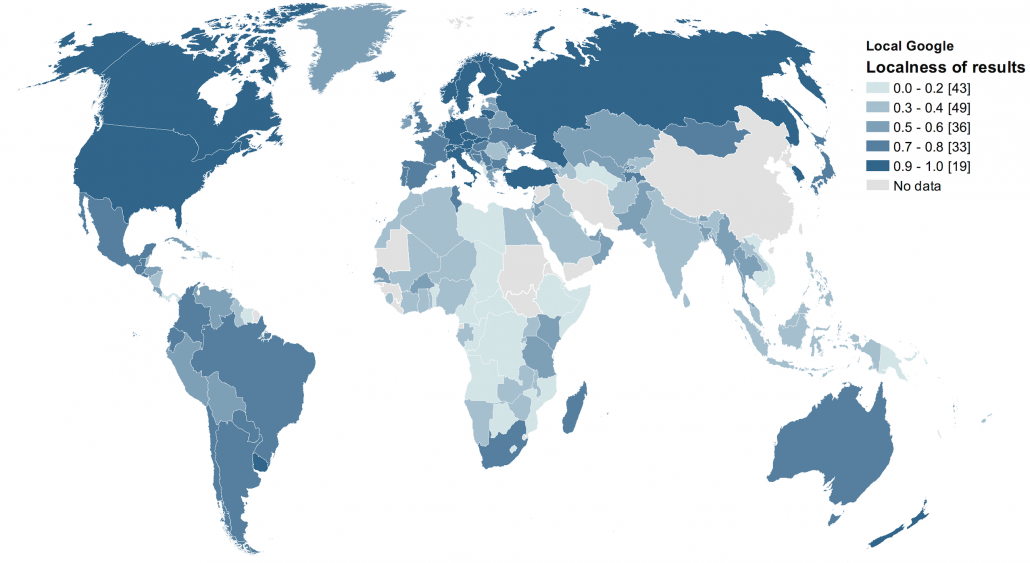

This investigation of the geography of Google Search results shows that wealthy and well-connected countries tend to have much more locally produced content that is visible about them than poor and poorly connected countries. Even cities located in countries with huge populations such as Lagos show a tendency toward having relatively little local content about them in Google Search results. This means that a user in the United States or Germany searching for cities is far more likely to be given access to locally produced content than a Tanzanian or Cambodian.

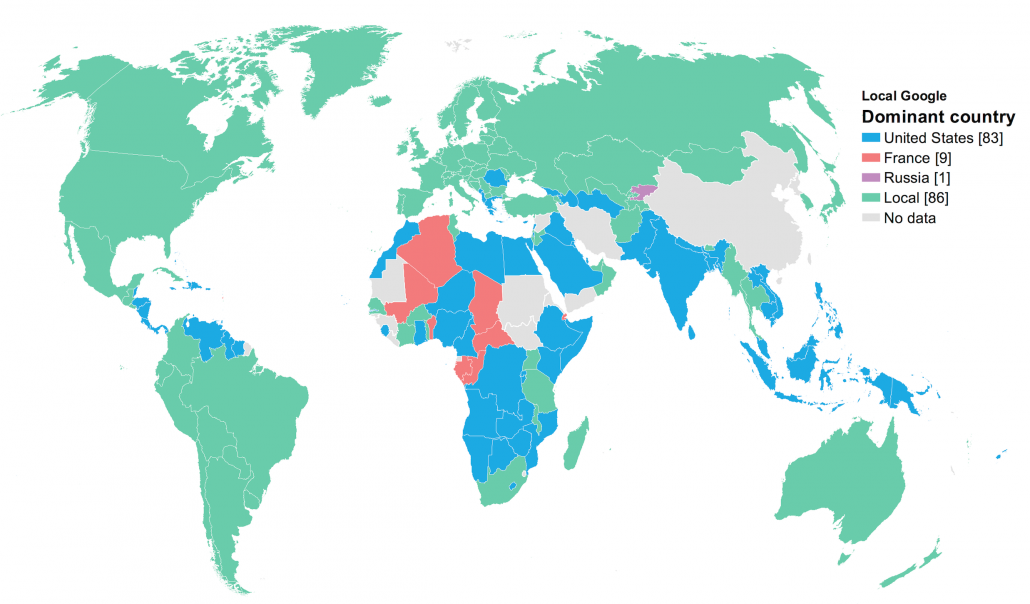

In our empirical study, the results of only eight countries in Africa (and four low-income countries: Tajikistan, Madagascar, Burkina Faso, and Tanzania) have a majority of content that is locally produced. This gives rise to a form of digital hegemony, whereby producers in a few countries get to define what is read by others. The United States, in particular, is a dominant content-producing force, even when excluding Wikipedia, which is a highly visible U.S.-based but globally assembled resource (Figures 10 and 11). In the results for sixty-one countries, the United States supplies over half of the first page content on Google. This means that not only are U.S. Internet users surrounded by an extremely locally produced Internet, but U.S.-produced content is highly visible in much of the rest of the world. This does not necessarily mean that the United States is an informational hegemon everywhere in the world, however. France has a somewhat smaller sphere of influence, mainly limited to countries in Africa, whereas Russia produces a visible effect only on results about Kyrgyzstan (see Figure 10).

It is important to note that, because our data set focused only on capital cities, caution should be taken when extending the results to higher spatial granularities. Our localness indicator does not take into account the actual interaction of users with search results and the variety of devices and media across which individuals currently access search engines. Despite the precautions that we took to access representative samples of search results, some noise is still present and some results might show high volatility. Much more empirical work is needed to study finer patterns within countries and to build more accurate models to investigate the consumption of geographic information on search engines in different geographic locales.

More broadly, the point remains that most countries in the Global South continue to be defined by a diverse range of sources originating from a diverse range of places. The issue here is not that Internet users are exposed to a diverse range of sources from a diverse range of places—indeed, as Pariser (2011) noted, there are significant concerns for people and media ecosystems that lack access to such diversity. The issue is rather that that diversity itself has a particular bias and those sources tend to be almost entirely from the Global North; very few of the sources come from anywhere in the Global South. For instance, although the search results for Google’s Ghanaian page for its capital “Accra” include pages from six countries, five of them are firmly located in the Global North.

When looking at countries in the Global North, the results for Denmark’s capital are similarly diverse, with five out of six source countries also being located in the Global North. By contrast, a country like the United States suffers from the inverse problem: having almost no exposure to geographic representations made by nonlocals.

The key question, then, is why. What explains this informational hegemony, or the dominance of the Global North in producing digital representations about not just themselves but also about much of the Global South? Interestingly, our explanatory models indicate that network connectivity and economic development in a country are not enough to make content about that place more local in Google Search results. The presence of a strong publishing industry, using SciMago publication data as proxy, is the strongest predictor of the production of visible online content. The importance of the h-index in the model also shows that the impact of scientific publications is a better predictor of localness than the mere number of publications. Thus, we suggest that socioeconomic systems that produce high-quality research also tend to produce highly visible online content. There are no countries in the Global South that score well on such metrics, and there are consequently no countries in the Global South that play a major role in constructing contemporary Internet geographies.

Having taken a first step in this direction, more quantitative and qualitative research is needed to better understand why exactly scientific knowledge production explains so much of the variance in Google’s local digital representations. More relational variables and different spatial granularities will have to be considered. Until then, though, we hope that the finding that wealth and network connectivity alone are not sufficient factors is worth demonstrating, especially for Internet activists who hope to bring about more genuinely participatory and representative digital environments. This point increasingly matters because places are ever more defined by their digital presences, and the ways in which places are represented digitally increasingly shape how people understand and reproduce those very places (Graham, De Sabbata, and Zook 2015). Google plays an enormous role in constructing these digital representations of places. Because of their dominant role in mediating a majority of the world’s Internet use and the fact that few people ever explore beyond a first page of search results, they essentially determine which digital augmentations of place are made visible or invisible, with tangible effects in the physical world.

This article demonstrated that Google Search results are actively reproducing new forms of informational hegemony around the globe. A few countries in the Global North play an inordinately large role in defining the digital augmentations of the Global South. Google’s methods for ranking and representing are notoriously opaque (Vaidhyanathan 2011; Graham et al. 2014), but we do know that two key factors come into play. First, much of the reason of the lack of local voice in the Global South is likely simply because the production of Internet content happens at a much lower rate compared to that in the Global North (Graham, De Sabbata, and Zook 2015). Second, since the company’s creation in 1998, Google’s algorithms have tended to favor highly central Web content: Pages linked to by a lot of other pages are prioritized, and those largely ignored are demoted in the rankings. This creates a worrying situation whereby it becomes difficult for those on the information peripheries to break out of their digital marginality.

Building on earlier research looking at the geographies of information, this article has analyzed not just where digital content comes from but how it is ranked in the world’s most powerful digital mediator. Much more will need to be done to understand not just the ways in which people are afforded voice about their own communities and countries but also the myriad factors that serve to amplify or constrain it. Until then, we hope that other research can use this article as a beginning to ask not just why some parts of the world are denied locally produced representations but how we might bring about more representative and participatory digital augmentations of place.